Why are Catalytic Converters a Target?

On 16 May 2023, cargo thieves attacked and hijacked a truck travelling en route from Port Elizabeth to Cape Town, South Africa. The truck driver was shot and seriously injured.

After taking control of the vehicle, the offenders used a GPS jammer to delay security monitoring services and drove the vehicle to a remote location to offload and steal its cargo.

The target: catalytic converters.

This is just the latest in a series of high value and violent attacks on automotive supply chains in the Europe, Middle East & Africa (EMEA) region, with catalytic converters the prime target. In the last 18 months, thefts of catalytic converters have been reported to the TAPA EMEA Intelligence System (TIS) in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom as well as in South Africa. While most crime reports stating this product type do not share financial loss data, these are known to be significant, high value incidents.

Yet, as with so many other types of cargo crime, the number of recorded thefts is believed to represent only a small minority of the total number of incidents taking place.

TAPA EMEA invited Julian Köhle, Government Affairs Manager at The International Platinum Group Metals Association (IPA), which represents the interests of the global Platinum Group Metals (PGMs) industry, to tell us more about this fast-growing cargo crime trend…

Police in many countries are dealing with increasing rates of catalytic converters thefts because they contain valuable Platinum Group Metals (PGMs), such as rhodium, platinum and palladium. Rhodium is particularly lucrative, peaking at almost 28,000 Euro a troy ounce (31.1 grams) in May 2021, and PGMs in general have seen a significant increase in value over the past decade.

Consequently, criminals have seized the opportunity to profit from stealing catalytic converters, leading to a surge in theft incidents worldwide. Thieves can easily steal automotive catalytic converters from vehicles, and since the converters are not readily traceable, there is a lucrative market for these stolen parts and their valuable content. The catalytic converter is a crucial component of a vehicle’s exhaust system. In the catalytic converter, platinum, rhodium and/or palladium are coated onto a ceramic monolith core with a honeycomb structure, serving as catalystsresponsible for reducing harmful emissions by converting toxic gases into less harmful substances.

Currently, around 70% of global industrial demand for PGMs is used for manufacturing catalytic converters. PGMs in the catalytic converter are not consumed and once a vehicle is scrapped, the PGMs become available for recycling carried out by professional refining companies who use advanced processes for extracting and separating PGMs from catalytic converter scrap. Catalytic converter theft poses a significant threat not only to individual vehicle owners but also to the overall economy.

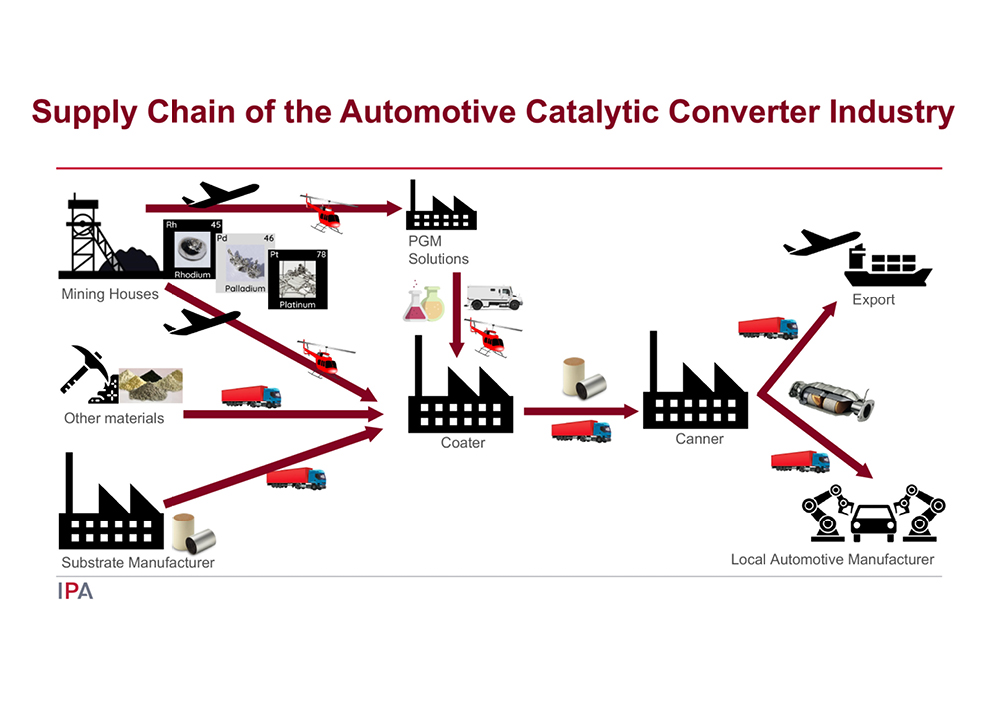

The supply chain for manufacturing a catalytic converter includes transport from “coaters” to “canners” and onwards to automotive manufacturers. The coaters apply the PGM containing so-called wash coat to the honeycomb-like ceramic interior of a catalyst, while the canners put the honeycomb into the catalyst’s metal housing.

There are some hotspot countries where converter thefts are spiking to an extreme level, but reports show that more and more countries are being affected, making this a global crimewave. However, despite its increasing prevalence, one major hurdle in tackling this issue is the lack of comprehensive data on thefts, hindering efforts to understand the scope and severity of the problem.

Modus operandi

There are currently two modus operandi observed.

- Making the most headlines is theft of catalysts by thieves that slither under cars with electric saws and can have the catalyst cut off within half a minute or three minutes maximum.

- Less extensively covered is criminals targeting production and shipments of new catalytic converters as well as recycling facilities specialised in recovering PGMs from spent catalysts.

What happens to stolen catalytic converters?

Private investigations have shown that stolen automotive catalysts from cars are not offered as spare parts on illegal markets but will be sold off to certain scrapyards which do not investigate the source of origin. If newly produced catalysts are stolen in bulk from production sites, transport trucks, or warehouses, it is likely that they will be immediately crushed and mixed with material from spent catalysts to disguise their origin, and then sold to legal businesses for further refining. The PGM industry is concerned about the likelihood of illicit material finding its way back into the legitimate market as this undermines the industries’ efforts to make the PGM supply chain more transparent and traceable.

Epidemic of catalytic converter thefts

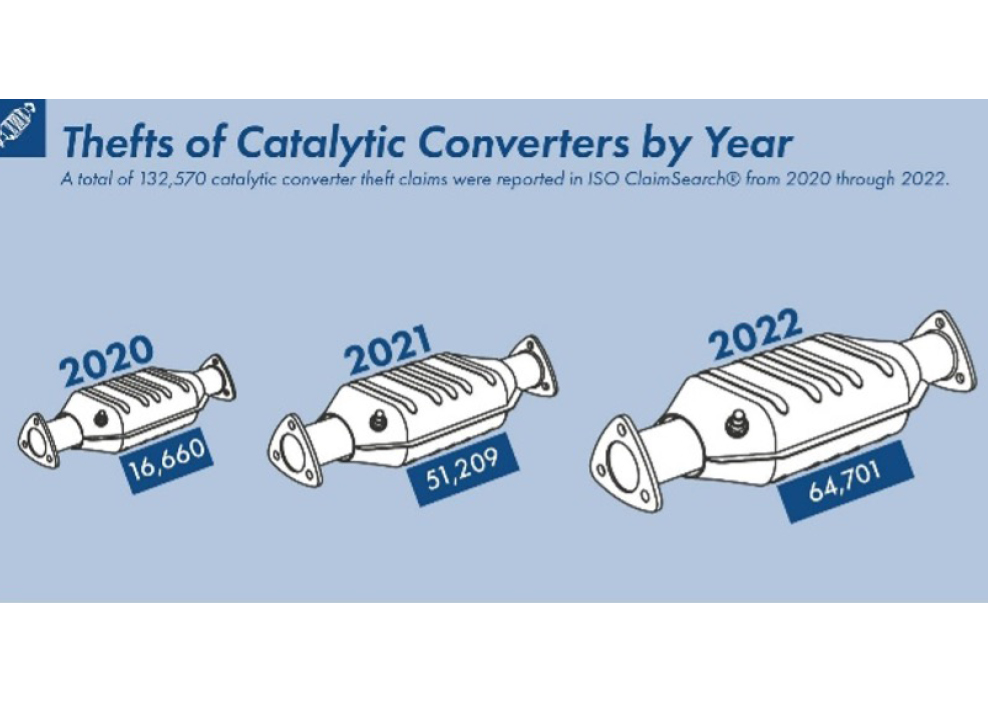

For the first modus operandi, the U.S. National Insurance Crime Bureau, a non-profit organization dedicated to identifying, preventing, and deterring insurance fraud and crime, estimates that thefts of catalysts from cars increased by 1,215% between 2019 and 2022. In total, the United States experienced more than 64,000 catalytic converter thefts in 2022. Leading the country are California and Texas, which saw more than 32,000 catalytic converter thefts last year. Often metal recyclers pay between $50 and $250 for a catalytic converter and up to $800 for one removed from a hybrid vehicle as their converters are less corroded then those found on diesel or gasoline cars. Replacing stolen catalytic converters can cost between $1,000 and $3,500 or more, depending on the type of vehicle. While thieves can hit any car, officials say prime targets have been SUVs and fleet vehicles, such as trucks and buses, which are easier to slide underneath, and Toyota Prius hybrids.

And they almost never get caught. In the UK, tens of thousands of catalytic converter thefts are going unsolved, with only 1% of cases resulting in someone being charged, according to a BBC article [https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-64057742] while the U.S. Chicago Sun-Times found that of 17,000 reported thefts only 0.2% (34) ended with an arrest.

However, in November 2022, U.S. authorities informed that the Justice Department arrested 21 people suspected of belonging to a theft ring that made millions of dollars from stolen catalytic converters. A team of law enforcement agencies at the local, state and federal levels seized hundreds of millions of dollars in assets from the defendants, including homes, bank accounts and cash, cars and jewellery. The federal government is seeking $545 million total in forfeitures.

While law enforcement in the U.S. made progress in uncovering organised criminal groups linked to the theft of catalysts, the Swedish authorities are facing an explosion of catalytic converter thefts. Two years ago, there were less than 100 cases per year in Sweden, but now it has reached 7,500 cases a year, an increase of nearly 10,000% according to the insurance industry. Insurers in Sweden are calling for increased funding for customs to help stop stolen items from being shipped out of the country.

Effective counter strategies require information

It is important to point out that reports on catalyst theft in various countries are just a snapshot of a generally underreported crime as in most countries the number of unrecorded cases is likely to be very high. The lack of comprehensive data on catalytic converter theft presents a significant obstacle in addressing this issue effectively. Law enforcement agencies face challenges in gathering accurate statistics and analysing patterns of theft due to the absence of a centralized reporting system. The absence of reliable data on thefts also hampers efforts to implement targeted preventive measures.

The positive result of data driven investigations in the case of the U.S. theft ring demonstrates the need for information collection. Because without a clear understanding of the regions and demographics most affected by catalytic converter theft, it becomes challenging to allocate resources and develop effective strategies to combat the problem. In Germany, for example, there are no statistics on theft of catalytic converters available from the insurance industry, nor from federal police, ministries or other law enforcement authorities. One reason might be that in Germany and in many other jurisdictions, catalytic converter theft is not categorized as a separate crime but instead falls under broader vehicle-related offenses (“theft of car parts”), making it difficult to track and measure the true extent of the problem. Only the ADAC, the German automobile club that provides roadside assistance to its members, has published data on catalytic converter thefts in Germany based on statistics from ADAC road patrol. The breakdown helpers were called 1,038 times in 2022 because of stolen catalytic converters – significantly more often than in previous years with the number of unrecorded cases anticipated to be much higher. In 2021, the ADAC recorded 959 cases, and in 2020 ADAC counted 420 stolen catalysts.

Call for legislation

Curtailing catalytic converter theft requires a multi-faceted approach involving collaboration between law enforcement agencies, government bodies, businesses, and the public. In some countries, legislative efforts are underway to address the rising number of catalytic converter thefts. New bills and amendments are being introduced to increase requirements of catalytic converter sellers, impose due diligence obligations on metal recycling entities, and establish penalties for unauthorized sellers and buyers engaging in fraudulent practices related to catalytic converter purchases. The International Platinum Group Metals Association (IPA) welcomes the push by several industry groups for a federal licensing requirement in the U.S. for anyone buying or selling catalytic converters. It should also be noted that recycling businesses, which recover precious metals from spent automotive catalytic converters and then send those PGMs to refining, are increasingly targeted by criminals.

Transport of catalytic converters under attack

As mentioned, less extensively covered by news reports is the second modus operandi with criminals targeting cargo transports of catalytic converters.

In Europe, thefts of catalytic converters during transport mostly happen on the road when drivers park their trucks in an unsecure area, following resting time restrictions applying to their trip. To address this, some companies in the PGM industry started using logistic companies with secured trucks who were advised to use secured parking places only. This had a positive short-term effect on the overall number of incidents. However, in February 2023, a transport of catalytic converters was attacked at an unsecure truck parking in South Germany with catalysts of a value of 1.4 million Euro stolen.

Another new hotspot in the cargo crime risk landscape for PGMs is South Africa, where since at least 2020 the entire value chain of this industry, from mines through to production and export, has come under siege from armed, violent truck hijackings targeted at theft of the raw materials and finished products containing PGMs. Since 2020, the PGM industry has witnessed a severe increase of thefts of catalytic converters, mainly during their transport or when stored at warehouses, very often including a high level of violence. For example, several hijackings took place over the last years where entire trucks with cargo worth millions of Euros were stolen. In May 2023, a coordinated aggressive attack on a catalyst transport in the region around Port Elizabeth ended with one security officer shot and severely wounded while the criminals took off with products worth 2.3 million Euro. Parts of the stolen material were later recovered which reduced the loss to 1.5 million Euro. The local Nelson Mandela Bay Business Chamber in a letter to South African Minister of Mineral Resources & Energy explained that these robberies are the work of internationally well-connected organised crime syndicates using sophisticated technology to track vehicles and jam security and tracking devices, and with the means to offload, transport, store and ultimately smuggle the goods out of the country. In addition to the human costs of loss of life or serious injury, these crimes threaten investment and employment security, and impact on the national current account, taxation revenue and foreign exchange earnings. Despite the actions of the police, working in concert with the industry and private security services, these hijacking-driven crimes are continuing to escalate, and several lives have been lost.

Collaborating to tackle the illicit trafficking of stolen PGMs

To prevent illicit PGM material from getting back into the legal supply chain, it requires collaboration among industry stakeholders, law enforcement agencies, and regulatory bodies to share information and intelligence on theft and trafficking activities. This can facilitate early detection and prevention of illicit transactions. Stakeholders should support efforts for awareness raising among the public, industry workers, and law enforcement personnel about the issue of PGM theft and trafficking. Possible options could involve training programs, educational campaigns, and sharing best practices to help identify and report suspicious activities. Law enforcement agencies investigating this type of crime should clearly understand that these are not isolated, unrelated cases, but well-planned actions of criminal groups. Consequently, international cooperation and coordination to combat cross-border PGM trafficking should be fostered. This can involve sharing intelligence, harmonizing legal frameworks, and collaborating on joint operations to disrupt illicit networks. When it comes to sharing of information on PGM related criminal incidents, the TAPA EMEA Intelligence System (TIS) database is a valuable tool for creating a collective and informed response to the challenges posed by catalytic converter cargo theft. Furthermore, it is important to collaborate with the scrap metal industry, which often acts as a conduit for the sale of stolen PGMs. This should be supported by regulations that require scrapyards to maintain detailed records of purchases and enforce stricter accountability.

In conclusion, the globally increasing threat of catalytic converter theft poses a significant challenge to vehicle owners, the PGM industry, law enforcement agencies, and policymakers worldwide. The lack of comprehensive data on thefts is a major obstacle in addressing this issue effectively. Furthermore, cooperation between law enforcement agencies, scrap metal dealers, and recycling centres is crucial to track and trace stolen catalytic converters. Implementing stricter regulations and requiring sellers to provide identification and proof of ownership can help discourage the illegal trade of these stolen parts. By fostering collaboration and sharing information, stakeholders can work together to disrupt the illicit market for stolen catalytic converters and PGM containing material.

About IPA

The International Platinum Group Metals Association (IPA) represents the interests of the global Platinum Group Metals (PGMs) industry. IPA serves as a platform for exchange with several committees that deal with areas such as Sustainability, Health and Environment Science, as well as Security. At the IPA Security Committee (SecCom), the heads of security of the IPA member companies exchange on the latest challenges, crime trends and lessons learned.

About the Author

Julian Köhle is Government Affairs Manager with ten years of experience working in the PGM industry for the IPA. Holding a degree in peace and security studies from the University of Hamburg and having worked in corporate and marketing communications, Julian specializes in monitoring political processes relevant for member companies of the IPA, and in communicating the interests of the IPA membership to stakeholders. His current focus is on creating awareness of the ever-increasing threats to the PGM supply chain from organised crime and cross-border criminal networks.